Home | Contents | Kite Catalog | Line, Swivels and SnapAway Kits

Kite Training of Falcons

It's probably easier than you think

Unlike old-fashioned kites, these kites fly to steep flying angles in exactly the sort of winds ideal for training falcons.

Many people have said they didn't think they could manage the kite flying aspect of this. Their fear is rooted in a perception or dim recollection of a time long ago when all attempts to get a kite flying were met with disaster. This depressingly common state of affairs is most likely caused by the fact that commercial kites are made to sell, not necessarily to fly (with thanks to The Popular Recreator, 1872-3). Rest assured that a decently made, well designed delta kite is very easy to get aloft. There are no adjustments. Assembly is just one cross-piece to insert. They fly themselves. Launching is straightforward, usually no more difficult than letting the line run out with a little drag. Once they're up, they stay put, and can be tied off to a ground anchor.

Many people have said they didn't think they could manage the kite flying aspect of this. Their fear is rooted in a perception or dim recollection of a time long ago when all attempts to get a kite flying were met with disaster. This depressingly common state of affairs is most likely caused by the fact that commercial kites are made to sell, not necessarily to fly (with thanks to The Popular Recreator, 1872-3). Rest assured that a decently made, well designed delta kite is very easy to get aloft. There are no adjustments. Assembly is just one cross-piece to insert. They fly themselves. Launching is straightforward, usually no more difficult than letting the line run out with a little drag. Once they're up, they stay put, and can be tied off to a ground anchor.

Dan, I really enjoyed your web site and could write a short stint about experiences with "Dennis," a male Saker who never really excelled, but I managed to get him to 1000 feet in a week. He climbs to that height in less than 5 minutes under all conditions and is majorly committed to his task and gets excited with the sound of the rustling nylon. He was extremely scared of the kite at first so it was by no means a completely simple task, but once the connection had been made he was dead on. I will wait and see how things develop as there is more than just getting a bird to mount, but it might be interesting to see whether I can turn around an old dog to some new tricks. So far he has developed enormously, but if I can sustain the high mounting he might start catching things consistently which would be quite a novelty for Saker Falcons in Britain. Best wishes, M.G.

Dear Dan, I am still having fun with my kite, and it's now being put to good use with a female peregrine from a very good pedigree. It is making training less complicated and fitness achievement is a doddle. I was away for a month and she had not been flown at all. I came back and put the kite up to about 600 feet and she mounted to it without hesitation. I am able to fly her at a higher weight as well, as she seems much happier going out to the kite than coming in to me. She doesn't go to such enormous heights without the kite but her pitch is still very respectable and should improve with hunting - however, she will mount to the kite whether there is a lure on it or not, so at the very least it is a clear guide for her to gain height even if there is no obvious reward there. Best wishes, M.G.

Can anything go wrong?

Murphy's Law applies to kites, just as it does in every other aspect of life. Incredible as it may sound, some people (in the UK at least) try to fly kites without taking wind direction into account - we've seen this many times over the past 30 years. Kites won't fly unless the wind is at the kite flyer's back.

A common beginner's mistake is misjudging the wind strength. With a little experience kite flyers learn to match kite to wind.

The line is equally important; you won't have steep flying angles in light winds unless you use light line, and you risk losing even the right kite if you put it up in too much wind on too-light line.

As with fishing good, well-tied, knots are crucial. Use knots with as close to 100% efficiency as possible - not just for attaching swivel clips, but for all joins, rings, or loops anywhere. Always keep an eye out for nicks or frayed spots in the line and cut them out before applying strain. And, please, don't clip sharp clips directly on to flying line.

Remember: people, young and old alike, have been flying kites for thousands of years. With a good kite it's not difficult.

For full reports on falconers' experiences see:

- Lure your Falcon "Up"

- by Roger James

- (from "The Austringer")

- and the report from Matt Gage

As all of the information I have has been passed on to me by falconers, there are many individual variations on these methods and approaches. There is a consensus on one point: unless you want to use a radio-controlled release for the lure(s), a simple, low-tech setup is ultimately very reliable.

The diagram below shows a popular setup used here in the UK. The original sketch was provided by Debbie Davenport of The Falconry Centre (Hagley).

"The clip is an ordinary wood or plastic clothes peg." You can either file it or build it up with epoxy so it's got just the right release tension.

Debbie recommends a 1½ inch key ring, but these are difficult to remove - impossible with one hand. Roger James uses a mini carabiner, which he can unclip with one hand and then swiftly clip to himself as a precaution. Click the picture for a closer look.

"The peg is on a loop of cord about 20 inches/50cm long, tied to a fishing swivel-clip.

You clip this loop on to the kite's towing ring, pass the flying line through the key ring, and clip it to the kite."

Alternatively tie a non-weakening loop on the kite line somewhere further down from the kite. (Roger James uses about 8-10 feet; a falconer who did extensive testing says 80 feet is about right; closer than 80 feet and the lure can pull the kite's nose down, while beyond 80 feet it can swing the kite line independently - both hampering control. At 80 feet the kite and line fly in unison as if there wasn't anything extra attached.)

Helping Roger James out at a falconry display I attached one of Roger's small metal terry clips (made for cupboard doors) to my line about 80 feet down from the kite using a Prusik Knot. Clipped around the kite line and held by the terry clip was the mini carabiner on the end of Roger's lure line. This utterly simple, makeshift setup worked flawlessly (after tightening the clip's grip with a little judicious bending).

Helping Roger James out at a falconry display I attached one of Roger's small metal terry clips (made for cupboard doors) to my line about 80 feet down from the kite using a Prusik Knot. Clipped around the kite line and held by the terry clip was the mini carabiner on the end of Roger's lure line. This utterly simple, makeshift setup worked flawlessly (after tightening the clip's grip with a little judicious bending).

A more permanent arrangement would be one or more Blood Dropper Loops staggered along the kite line for attaching small clips or clothes pegs or whatever fits the ring or carabiner on the lure line.

Alternatively, the clip could be on the end of the lure line with an alloy (or perhaps neoprene) O-ring on the kite line - anything as long as it's the right size for the clip and doesn't damage the kite line (you do not want to lose a kite by damaging the line with bad knots, sharp edges on clips or rings, or wear-and-tear). The main thing is that the clip fits the ring or carabiner so that it won't come off during the flight, yet isn't so tight the birds can't release it.

I have heard of lure lines of 30 inches/90cm to 30 feet/9m long, so obviously it isn't critical. In her notes, Debbie says "If the lure line is too long, drag makes it harder for the bird to detach it. This also depends on wind conditions." Because of drag long, heavy lure lines may come un-clipped during launches and climbs. Roger James' lure line was about 8 feet long the day we used my Skyhook for his display at the Brecon Beacons Visitors Centre.

"Falconry is an ancient tradition in the Middle East. We have been selling falcons to wealthy customers for about ten years, and sent out 14 birds last year. The kite is very good for getting them into shape and helping exercise adult birds. I have been told by a customer that two of the falcons I trained on it are the best hunters they have ever had."

- C.J.G. (Welsh Hawking Centre)

Another benefit from kite training is that lost birds can be enticed back from beyond transponder range (or re-captured after being tracked down) by sending up a kite with a lure. "I want a bright colored kite in case a bird gets lost - put up the kite and it acts like a magnet."

Dave Scarbrough in America describes a different setup.

A quick-link, mini carabiner or "carbine" clip, on a 6 inch/15cm cord, and a 5 foot/1.5m lure line are fastened to an adjustable "line release" (from fishing tackle shops).

Somewhat similar clips are available from me; the principle is the same, except they don't clip directly onto flying lines. See sketches of SnapAways here for clarification. These SnapAways don't have to be attached to or near the kite; they can be attached to a Ringboom practically anywhere on the kite line.

Some distance below the kite, hook on the krab (or quick link) and clip the clip on as shown. This system allows for resetting lures without having to land the kite - by walking the line down, lures can be clipped on at any point while the kite is flying.

Both setups train the birds to come straight down with the lure, rather than fly off with it. When the bird takes the lure, someone has to "walk" the line down (by walking towards the kite) to keep it vertical - so the bird can slide down. Sometimes courageous falcons struggle to fly away to the side before they discover the easier quick way straight down, but this should take no more than a couple of weeks.

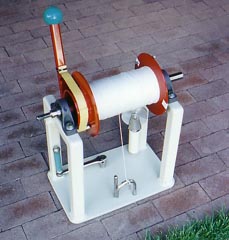

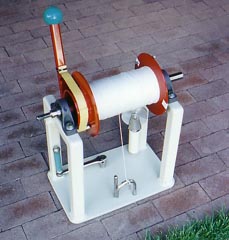

Gerry Plant uses this little downrig, based on one originally devised by Andy Hollidge. It is utterly reliable. The little pulley has ball bearings.

Gerry Plant uses this little downrig, based on one originally devised by Andy Hollidge. It is utterly reliable. The little pulley has ball bearings.

It doesn't open, however, which means it can't be just unclipped from the flying line.

A completely different method utilizes a stainless steel pulley, the sort used on the tips of deep sea fishing rods. The pulley is attached to the kite line and the kite is flown high at all times. A second line through the pulley hauls the lure up, just ahead of the bird being trained.

| A Falconer's Knot, tied in reverse so a falcon can pull the lure free, can be used instead of contraptions or gizmos. |

Practical considerations determine which method to use. If you don't use a link that opens and shuts, you have to feed the end of the kite line through a ring; you're not going to want to feed 80 feet through every time. Regardless of setup, the feedback I get is is overwhelmingly positive. Time and again skeptical falconers who had either doubted it would work, or doubted their ability to fly kites, have phoned me within 24 hours with amazing success stories. It isn't so much the falconer being particularly clever; this method just really motivates the birds - they do it practically all by themselves. As long as they're going to the lure, they pretty much take to it instantly. I have heard about hooded birds getting excited at the first sound of rustling ripstop, and how they develop their own strategies and unique plans of attack. As soon as the hood is removed, the bird cocks its head, marks the kite, and takes off - using a different approach every time. People are using this technique to not only train and exercise their birds, they're using it to break new ground. Slope-soaring hawks like Harris Hawks are being taken up very high just for the fun of it; Kestrels are learning to stoop like Peregrines, diving like air-to-ground missiles (you may need a remote release for this). There are new stories every week.

Practical considerations determine the answer to this question - what's easiest for you with the various bits and pieces you have at hand. Some think that training with lures attached well down the line from the kites would not necessarily teach the birds to directly associate kites with food, or that the kite itself might worry the birds and so put them off. I've been assured that such worries are generally groundless.

It is really more a question of what is easiest to manage. For instance, you might be in an area where the winds are so smooth you can leave the kite flying while fixing things to the line lower down; on the other hand, you may have to feed the end of the line through a ring - then it's practically impossible not to have it close to the kite. From the standpoint of stability, one falconer who's done a series of tests found that about 80 feet down the line from the kite is best for the flying; even with a heavy lure, lure and kite fly together as a unit, without fighting each other.

Feedback & opinions

I have heard from "old hands" who had wondered how some of these beginners had managed to get their birds to such a high pitch; I have heard of kite-trained birds being advertised at 50% higher prices than normal. I've been told by successful breeders they couldn't possibly train all their birds without the kites.

The birds learn tenacity

Opinions differ about the virtues or otherwise of one method or the other. The majority of falconers use a ring or link of some sort to keep the lure line on the kite line, essentially for teaching the birds to come straight down - otherwise you're just teaching them it's OK to fly off into the boondocks. This technique also teaches the birds to be tenacious. Things don't always go smoothly; the bird can get a little bit stuck on the way down, and the trainer must walk the kite line down (typically with a small carabiner in a lanyard) a little to keep it vertical. The birds may let go and come back for the lure several times; but in the end the birds learn never to give up, and they become supreme hunters of larger targets.

Untethered, free-flying lures

But others use an alternative method - whole dead crows or pigeons (or a normal lure weighted with lead shot or sand) dropped by radio control just before the bird arrives. Thus it learns to dive. The weight of the lure is meant to prevent long glides, but larger, stronger falcons can lock their wings out and still end up a very long way off, eat their fill, and then take off again before they can be reached. They can also injure themselves when they hit the ground. But I have also had falconers swear it's the safest way; that they've seen or heard of a bird that got tangled up in the flying line. With a radio release, when the lure is dropped the flying line shoots up and out of the way, so there's no chance of a bird coming into contact with it.

A common radio release setup consists of a small box with a trap-door bottom that opens on demand, dropping a snack. And no, I do not know how a falcon learns that there's a dead chick, out of sight, inside the box.

This is reportedly very good: instead of remotely releasing weighted lures, release a prey species, ususlly a pigeon, before the falcon reaches the lure. The kite would carry the lure at, say, 800 feet. When the bird reaches about 500 feet, the pigeon (or other prey species) is released. The bird spots the pigeon, turns and stoops.

This technique is related to the next one, using parachutes, but it has the advantage of training the birds to dive rather than fly off.

This method involves allowing - even encouraging - the birds to fly off. Clearly a technique for wide open spaces, this one allows the use of multiple lures without radio control.

The "model rocket" parachutes automatically deploy as the lure lines pull them free. The parachutes need to be big enough to provide sufficient drag to prevent the birds from flying further than about 300 to 500 meters. This method has the added advantage of building up powerful flight muscles. It's used where training birds to come straight down is not the priority.

As originally shown in "Hawk Chalks," the parachutes are packed into cardboard tubes made from paper towel (US) or kitchen roll (UK) tubes, held in by small Velcro tabs of some description (I've not seen this).

The multiple-lure setup described to me consists of three lightweight lures on 13 meter lure lines attached to parachutes fixed to the kite line about 10 meters apart, starting 10 meters down from the kite.

The potential hazards posed by seemingly distant powerlines, tall trees, etc. cannot be over-emphasized. Remember Murphy's Law, and stick to the wide open spaces.

One of my customers tried a parachute (on his falcon), and this particular bird would grab the lure and then lock his wings, facing the wind - allowing himself to drift backwards, pulled by the 'chute. Thank goodness for radio tracking.

I was sent this piece by a local falconer, but I don't as yet have the original source:

"What several falconers here in Oklahoma have developed was a system to release the kite when the falcon grabs the bait. We call it the Okie Rig.

This can be used on most kites, but I will be talking about a Little Bear. I have added an additional tow point to the very front of the kite. Attach kite line here. Going back down the kite line about three feet, tie a loop, I like either a surgeons loop or figure eight. Put this loop through the D ring tow point of the kite, just far enough to stick a nail through, so when pressure is applied to line, it holds the nail in place and will now fly. There is slack in the line from the nail to the front tow point now. Attached to the nail, another line, the bait line, what ever length you prefer, I use about fifty feet. Another short line is ran from the nail to the kite line so the bait line remains attached to the kite line. We're set, put the kite up say 1000 ft.

Walk down wind to a point where the falcon has to go up wind to the bait, so it learns when mounting it always goes into the wind. After she cast off, walk up to within 1000 ft of where the kite is anchored. She grabs the bait, pulls the nail, changing the tow point of the kite to the very front of the kite, it all comes down right where you are standing.

For me the advantages of this is always being able to release the falcon into the wind, no need to run the line down. When flying alone I often would take the easy way out and cast off the falcon at the kite reel, she flies down wind first before climbing back to the kite, after grabbing the bait I would run the line down until I met the falcon, unclip from the line and let the kite go. After she finishes her meal, then bring the kite down.

With this system the kite and line are down on the ground, not left to fight the wind until it gets pulled down. I roll up the kite, pick up the falcon, walk back to the reel, by which time she is finished eating and hooded, get the cordless drill out and wind in the line. It is done, it takes about half as long as other methods I have tried, slider or parachute. It is really an easy system to use."

The latest from Dave Scarbrough...

I am still flying the heck out of your Carbon Classic, Little Bear and Trooper... I now use a parachute release mechanism for the bait. The falcon pulls the whole thing off the kiteline and floats down to the ground in much less time than my former technique. The only hitch is, you have to find a very large open area to avoid hazards. The guy who came up with the idea told me the birds drop straight down. The first time I used it at 600 ft, the falcon went 600 YARDS downwind before touching down. Not exactly straight

down!

There is a rumor that birds can become "kitebound." A training regime whereby very young birds are trained as chicks to eat off a kite on the floor, then, when they're a little bigger, fed from a suspended kite so that they have to hop up to it to reach their food, followed by kite training where the lure is close to the kite is likely to result in the birds associating kites with food.

I have been assured this is unnecessary; birds learn to associate kites with food pretty quickly regardless of whether they were introduced to kites early or later in life. Through regular kite training, birds can become conditioned to respond merely to the sound of rustling kite fabric. When they take off, it's the lure, not the kite, they should be aiming for. If it's the kite rather than the lure, at least this will always useful should the bird be lost for one reason or another.

Dr Whirlwind, my kitemaker friend in Denmark, made a kite for a Danish falconer (one of about 6 in the country), and had this problem. He described it as the bird falling in love with the kite. Hunting with falcons is banned in Denmark, so the bird is in a different mind-set to begin with. Stooping for prey, or bringing prey straight down isn't the object.

The "treats" were attached with a bit of magnetic strip. Whether they were on the kite or the line unfortunately wasn't mentioned, but with the kite at 300 meters, the bird, having learned to associate the kite with snacks, would refuse to come down. The solution was to fly another kite at 7 meters. On seeing that, she would come down to it.

Whether a bird becoming kitebound is good or bad is a question for the owner, but it may depend (in specific cases) on how close to the kite the lure is. In my brief experience, the birds looked for a kite as soon as the hood came off, but went for the lure - not the kite - every time; from different directions and different angles, but always the lure.

Sending birds up to kites with no lures can be risky. While some birds might be unperturbed, with others you run the very real risk of irreparably breaking the fundamental bond of trust between bird and man. It is therefore essential to flush game as the alternative to the lure.

This mustn't be done too early in the course of the bird's training. The birds should be accustomed to flying to at least 500 feet on a regular basis - they have to be physically fit enough that they've got ample confidence. (Even so, certain birds, for example birds with Gyr or Saker blood, may prove too clever to bother, and may require preliminary training with a drop lure.) Thanks to Roger James

It has been found that birds who associate kites with food (or a fun game) return to them after being lost. I got quite a few enquiries after lots of people witnessed the return at dusk of a lost Lanner at the 1999 Falconry Fair. After an afternoon of fruitless searching there was still no telemetry signal, and though the stories varied, the kite was eventually put up very high, and the bird did indeed return. I have now heard many such stories, including several cases of errant birds, not so much lost as cheeky. Located with telemetry, they just wouldn't come down, and so it went for three days. But the kite proved irresistable in the end and all were caught safely and lived happily ever after. Now the kite is routinely employed for such last-ditch efforts.

The kite acts like a magnet. This is why many falconers prefer brightly colored, highly visible kites instead of light blue or grey ones.

The moment a young bird's flight matures

Once a bird is trained to go for a lure swung in the air, they'll go up to one on a kite line. The first time they spot a kite up there, they might pause for a second and think "what the bloomin' heck is that?" but then off they'll go. When he first got his kite, Roger James had a difficult falcon, a very poor flyer unable to climb to any height at all. All it could do was fly in a circle, hitch-winging all the time, centrigugal force preventing it from coming in to the lure. He put the lure about 20 feet up the kite line and the bird took it. He went 40 feet the next day, and about 80 feet the third, though still struggling. The fourth day, with the lure at a hundred feet or so, the little falcon started out hitch-winging again, flew down over the crest of a ridge, changed shape and shot upwards to the kite, flying like a true falcon.

According to Roger, the first hundred feet or so constitute a critical hurdle when first training young birds. At this stage they fly by fanning the wing and tail feathers out wide to get the most surface area, holding the wings out at right angles with the tips curling downwards (called "hitch-winging" in the US) - the falcon equivalent of a dog paddle. At this stage there's no characteristic sweptback falcon wing shape, no long narrow tail. After about a week of training they're strong enough to begin to fly around the sky with less of a sense of urgency. They're comfortable knowing there's a treat up there, and with fitness and confidence growing, can reach a hundred feet or so.

But beyond this point they find themselves panicking. Their flight is reminiscent of a hovering Kestrel, with the wings fanned out at 90°. The tail is fanned out wide. Maintaining height takes a lot of effort. It's time to sink or swim. They have to figure out the next stage for themselves, and it must be a memorable moment for both bird and trainer.

The penney drops; they suddenly see the light. The wings begin to change shape. The fanned-out feathers start to overlap: the tail narrows, the wings sweep back to take on the classic falcon form and the birds shoot forward like rockets, and from this point on they begin to truly master the skies. You can imagine the bird thinking "Why didn't I see this before?"

From this point on, the sky's the limit.

Further reading: Article on kite training from "The Austringer," the Welsh Hawking Club magazine.

Falconers require kites with special performance

characteristics. They need kites that can fly high and achieve unusually high angles in light winds - the same winds preferred by their birds. Few kites in history have had these special flying qualities. Delta kites in general made from lightweight spinnaker cloth have excellent light wind performance, but even so, it takes special refinements to the traditional delta design to achieve really steep flying angles at high altitudes. Other commercial deltas are based on a generic delta from 30 years ago; newer materials make them a bit better, but they still rely on added drag to cover the construction flaws inevitably present in mass-produced kites not individually scratch-built by a proper kite maker. That drag inescapably prevents steep flying angles; so too does the fact that in order to fly in a wide range of winds, to satisfy the general public, they have towing points set forward, which increases wind range, but significantly reduces both pull (=lift) and angle.

My deltas are built one at a time, with maximum precision and mathematically optimized for maximum lift in light winds (plus a small safety margin), or, if stated otherwise, the specified wind. Scalloped trailing edges* minimize drag in order to achieve the steepest possible flying angles.

*Falconer Andy Hollidge tested a wide-wind-range R6 (with flapped trailing edge for stability) and compared it with his scalloped Whirlwind. He found that the flying angle wasn't sufficient for his method (a newer carbon-framed version with improved performance has now been developed). Several others have found it very useful, though, in relatively breezy places at generally lower altitudes. The Welsh Hawking Centre used a large R10 with flapped trailing edges for suspending multiple lures dropped by remote control.

Precision in symmetry plus careful matching of wing spars assures straight and true flight. These kites are stable yet responsive - if they were difficult or awkward to fly they wouldn't have become as popular as they have (considering I rarely advertise) and I wouldn't keep hearing from satisfied customers. They are well stitched and thoroughly reinforced for durability, too.

Below are the kites falconers have been using. All are made to order, one at a time. Tried and tested, and proven satisfactory by falconers, they are available directly from:

Dan Leigh

54 Osborne Road

Pontypool

Gwent, Wales NP4 6LX

UK

Please note: These kites are not designed to withstand being flown in too much wind, dragged along rough ground, run over by off-road vehicles, stepped on, crashed into sharp and/or solid objects, or pulled through trees and off power lines, etc. They are not tools for excavating, plowing, quarrying or demolition. The fabric has to perform, which means the kites have to fly (and fly well), and a prerequisite for all flight is light weight. Even made from the best light weight fabrics available, light wind kites are nevertheless delicate structures; they are not indestructable and will only endure if handled with care and not subjected to abuse of any description.

Please refer to the ordering page for shipping details

VAT is charged at the standard rate of 20% and applies to EC only

US Stockists

For factory-made versions of XFS Deltas, Little Bears, Whirlwinds and Troopers |

Into the Wind

1408 Pearl Street, Boulder, Colorado 80302

tel: +1 (303) 449-5356

click here for... more info and page 23 of Into the Wind's 2009 catalog |

Western Sporting

730 Crook Street, Sheridan, Wyoming 82801

tel: +1 (307) 672-0445

|

Northwoods Falconry

Northwoods Falconry, PO Box 874, Rainier, WA 98576 USA

tel: +1 (360) 446-3212 |

| Polite notice: please do not try to contact me through Into the Wind - I am in Wales, UK, and will not get the message

|

Little Bear 76.5in x 47in/1.94 x 1.20m

Little Bear 76.5in x 47in/1.94 x 1.20m

light winds

Price: click here to go to the | Kite Catalog |

Please note: this design is intended as less expensive alternative to a Clipper for flyers on a tight budget needing an efficient light wind kite; as such, it is not meant for winds over about 8 to 10mph - it has the wrong fin geometry for windy weather. If flown in too much wind damage to frame and/or fabric can be expected.

Wildcard 88in/2.24m span; for high angle flying in breezy weather

Wildcard 88in/2.24m span; for high angle flying in breezy weather

Price: click here to go to the | Kite Catalog |

- very deep scallop

- sturdy and well balanced - good for 8 to 18 mph+

- fiberglass wing spars (a light wind carbon frame is being tested)

- this is the first choice of British falconers in windy locations

- flyer report: lifted 12oz to 500ft on 80lb line in 5mph wind

- assorted adjustable releases and clips

Whirlwind 100in/2.54m span; light to medium winds

Whirlwind 100in/2.54m span; light to medium winds

Price: click here to go to the | Kite Catalog |

- fiberglass wing spars

- made in standard and light carbon versions

- first flown in 1980, this is my most popular kite with UK falconers

- falconers report easy flights to 1,000ft

- assorted adjustable releases and clips

The kite is performing superbly in a range of winds and the angle adjuster helps a lot when winding down in strong winds. It is incredibly stable and will sit nicely overhead while you tie it up to a fence and proceed with training. Once you've made all your mistakes you can take it out alone and sit your birds on a cadge while you get it aloft. - M.G.

Clipper S solid color

Clipper S solid color

7ft 10in x 4ft 11in/2.39 x 1.49m

for light winds and thermals

Price: click here to go to the | Kite Catalog |

- capable of very high angle, high altitude flights

- carbon wing spars; 8mm carbon spreader strut

- falconers have discovered the advantage of the extra pull Clippers generate in light winds

- assorted adjustable releases and clips

Dan, I thought I was going mad spending all that money on a kite, then it arrived in the post and I was very impressed. I will definitely buy a Wildcard off you later in the summer. The signature was a nice touch. Thanks again, T.B. - Ireland

SPECIAL OFFER ...only while stocks of material last

Lightweight Clipper GPX Special

Price: click here to go to the | Kite Catalog |

- ½ounce sailcloth in all bright white, or with blue or red fin

- For 0.5 to 3 or 4 mph winds max

- Has thinner wing spars and spreader than standard Clipper S

Trooper RS - solid color

Trooper RS - solid color

Price: click here to go to the | Kite Catalog |

- flies up there with box kites

- special fin gives minimum pull for flying in medium to strong winds

- fin is double-walled and inflates in flight

- fiberglass center spine and rigid 8mm carbon spreader

CC345 S solid color

CC345 S solid color

10ft 8in/3.25m span; light winds

Price: click here to go to the | Kite Catalog |

The Carbon Classic is my personal favorite for training falcons. This super efficient kite needs almost no wind to fly, and it flies at an incredibly high angle. - D.S.

A falconer not far from here recently reported instant success with one of my smaller kites designed for a wide wind range.

His goal was 150 - 200 feet, in winter winds. The little R4 Ranger flew to a respectable flying angle on good quality 50lb fishing line. His clip was a clothes-peg filed to adjust release, as per this drawing .

This type of kite has extra stability built-in plus a medium-breeze towing point, which means they drift downwind more than scalloped deltas at high altitudes, but they can still fly straight overhead at lower altitudes, especially on thin, high-tech line.

The R5 Rustler has fiberglass wing spars and a heavy center spine; it's very good in blowy weather. Smaller kites in general are much easier to handle in windy conditions - remember, the force of the wind increases with the square of the wind speed.

R5 Rustler 70in/1.79m span; medium to fresh winds

R5 Rustler 70in/1.79m span; medium to fresh winds

A kite for anxiety-free flying - very stable

Price: click here to go to the | Kite Catalog |

The R6 Crosswind has the same geometry - it copes admirably with fresher breezes, but its lighter weight frame gives it good light wind performance as well.

R6 7ft 4in/2.24m span; for lightish breezes to quite windy conditions

R6 7ft 4in/2.24m span; for lightish breezes to quite windy conditions

Price: click here to go to the | Kite Catalog |

- Solid carbon rod wing spars

- Carbon spreader

- This kite may be good for falconry - it's meant to fly steadier than scalloped deltas over a wider range of wind speeds

SnapAway linkages can be clipped anywhere on the kite line

- Ringbooms do double duty as stays, helping to keep the lure line from twisting around the kite line.

| |

|

| On-line SnapAway Kit |

For price see the On-line SnapAway Kit in the main Line & Accessories catalog.

What's the difference between a Whirlwind and a Wildcard?

The Whirlwind has 1.35 square feet more wing area, the wing spars are about 4 inches longer, the nose angle is 4 degrees wider; the Wildcard has a deeper scallop and its towing point is set further forward for fresher breezes - the Whirlwind's fin has a light wind towing point. The Wildcard's spreader is set further towards the front (nose) of the kite, which means it can be one sixteenth of an inch smaller in diameter (yes, even though it's for stronger breezes). Finally, the Wildcard is not a true standard delta - it's got an extended keel where the wing root extends back 4 inches beyond a line drawn between the wingtips. Other parts are the same stock size.

In plain English, the Whirlwind goes to a steeper flying angle and there's more tension in the line. The two kites' wind speed ranges overlap. However, "strong" is a relative term, and there are many places where the "strong breezes" are just too strong for a Whirlwind (the kites are well nigh unflyable). The Wildcard comes into its own for these flyers. Yet a Wildcard has also lifted a 12 ounce radio-release lure to 500 feet in a 5mph breeze.

The Whirlwind will have a theoretically steeper flying angle than a Wildcard. There will be more pull on the Whirlwind's line in light winds, and therefore less sag in the line, but the Whirlwind would be on 50lb line, while the Wildcard would usually be on 80lb or more, flying in a bit more wind. Both kites suit setups using a ring coming down the line; they just give a similar performance at different wind speeds.

Color choice and frightening birds

Opinions about color depend as much on preconceived notions as anything else. Falconers have ordered (and used successfully) every color I've ever stocked - bright, dark, and pale colors. Initially, many falconers requested pale or neutral colors like light blue or grey. Falconers were worried that a dark delta shape might frighten their birds, and there are a few reports of black deltas scaring young birds, but they got used to them after a few days. One bird reportedly flies above and around a black Clipper, scolding as if it were some huge raptor, but still takes the lures. It's not a problem; it's just part of the game.

Report of a falcon being utterly terrified by a kite (color unspecified):

At first her owner didn't have a clue what could be done, but he managed a cure by suspending a kite for one week in the room where she's kept, so she got used to it. After that it was just a few days before she was enthusiastically climbing to over 500 feet (something she'd never done before).

Some falconers feel that, in theory, strong-colored kites might end up attracting the birds' attention more than the lures, while pale colors (difficult for human eyes, at least, to see) would not be distracting. With lures fixed on the flying line 150 feet below the kite, the birds are meant to focus their attention solely on the lures, not on kites. Actually, 150 feet doesn't look like much when seen from 800 or 1,000 feet directly below. Whatever the color, the practical advantage of having lures attached 150 feet or more down the kite line is that the kite can be left flying between jumps. Just walk the line down, re-attach the lure and let the line go. (Incidentally, a practical advantage to birds associating highly visible kites with food is getting them back after they've been lost - see below.)

Dave Scarbrough and others maintain that color, as a rule, does not matter. I've been told on more than one occasion how kite-trained falcons make the transition from kites of one color to another without skipping a beat. Gerry Plant says his bright, flo pink kites definitely do not scare his falcons (his lures are attached to the line well below the kite).

I have tested this first hand, too, at a Roger James public display. Roger's kite is a breezy weather Wildcard, and that day there was very little wind. The first flying-to-the-kite display had me doing a lot of running, with the kite at hardly any height at all and at a very poor angle, and to top it off I almost dumped the bird into some trees. My wife and I, meanwhile, had been flying lots of different light wind deltas that day, and so for the second display I thought we should try using something that would stay up there. Now, Roger asked me if I happened to have a light blue kite, and of course I didn't. (He knew his birds went clear across a wide valley to circle light blue paragliders, squawking at the pilots.) I happened to have my 12'8" Skyhook out so I tied one of Roger's little terry clips onto my line about 80 feet down from the kite, using a stopped Prusik Knot - very makeshift, but it worked without a hitch.

While red is probably the most asked-for color, one customer asked me to change the red fin on his kite to another color. He's got a bird that latches onto bits of red kite fabric and won't let go, clinging to it while trying to shred the material as if it were raw meat.

The birds soon learn to associate the sound of rustling fabric with pending excitement, so they're revved-up and ready to go before they have a chance to see what color the kite is - while they're still hooded.  The birds associate kites with treats, and they can get to know the color of their own kite, but they're primarily interested in the lures, and they can see whether there's a lure up there or not, even one the size of a thumbnail.

The birds associate kites with treats, and they can get to know the color of their own kite, but they're primarily interested in the lures, and they can see whether there's a lure up there or not, even one the size of a thumbnail.

At the 1999 Falconry Fair, a valuable Lanner was lost beyond transponder range. I don't know if it was a desperate last resort, a coincidence, or whether it was intentional or not, but that bird came back for a kite (or more precisely for the snack). Ever since, people have been asking what color shows up best in the distance. Well, most kites look black if they're far enough away; black kites always show up well in the distance to human eyes. Research has shown that birds' eyes are most sensitive to red and green. I have seen a small black kite (as a speck) out 8,000 feet, and a red one (as a speck) out 10,000 feet. Birds can see any color of kite far better than we humans can, so personal preference is as good a reason as any for choosing any particular color. One customer didn't want bright colors because he didn't want to attract kids!

Incidentally, as we are talking (hypothetically) about flying kites well beyond the regulation altitude limit (60 meters, about 200 feet in the UK), I like a bit of highly visible color somewhere on them in the interest of air safety. (Picture: two-color Whirlwind.)

Available colors

HUNTERS: A big black (or dark colored) delta will make game birds "go to ground"

There are high-tech flying lines available today made from aramid and coramid polymers that have virtually no stretch. They are very thin for their strength, and can be costly, but the prices are coming down. In my experience they can cut through flesh quite readily. But kites fly higher and to somewhat steeper angles using this stuff, and if a heavy lure and radio release is employed at least the birds will be safe. Leather gloves won't save your fingers, though, if the line slips through under a lot of tension. There is a story about a Flexifoil, a largish stunt kite, being flown on coramid or kevlar (aramid) line - it swooped down and sliced off the top of a pram, right through the aluminum tubes and everything!

Some lines are less durable than others; some have more stretch. As an ordinary kite flyer, I avoid monofilament fishing lines because you can't tell if they develop a weak spot, and so you never know when they'll suddenly break. They might be smooth and light, but you can't trust them. I usually recommend ordinary braided dacron flying line; it's a good compromise between durability, performance, cost and strength. There are expensive pre-stretched and coated versions of this made for fishing, but any line used for flying kites high soon gets stretched. One exceptional new line is Western Filaments' "TUF-Line," which has a hard outer coating enabling use without sleeving. It is not too expensive, either.

Handling kite line is always a problem. A little stretch in the flying line as it's wound in means a gradual build-up of compressive force on the drum; as this can crush even quite substantial reels, some garden hose reels haven't got a chance. The solutions falconers have devised range from the simple to the elegant. Many kite flyers and falconers are content with simple spools or wooden winders; for starting out one or the other is essential.

A few falconers have reported that garden hose reels tend to collapse if line is wound on with any tension at all. However, the construction of these reels varies. Another falconer tried all the electric fencing reels listed here and said he couldn't wind the kite in in strong winds, but that with a good, strong metal garden hose reel he was able to do it easily. Pegged to the earth, this has become his reel of choice and comes highly recommended.

Electric fencing reels

Many British falconers report success with these sturdily-built yet relatively inexpensive electric fence-wire reels made for farmers by Rutland Electric Fencing Co Ltd and Gallagher Powerfence UK Ltd available from argricultural suppliers.

The Rutland Model 19-190B Jumbo Reel is shown here (above, right) mounted on the optional Model 19-192C "Short Mounting Post" (recommended - Rutland's "Lightweight Reel System" doesn't clamp onto the post securely enough.)

There are also: - the Model 19-190R Jumbo Side Mounted Reel with a different clamp arrangement

- two more mounting posts: Model 19-192B for Jumbo Reel (1370m long) and Model 19-192A for Lock On Reel (1170mm long)

- two smaller sized reels: Models 19-191 Post Mounting SI Reel and 19-190A Hand Mounting Reel.

- Rutland Reels can be driven by a GOOD portable electric drill using the Rutland Model 19-300 "Reel Rewinder" attachment, shown above right.

These reels have been recommended, especially the Enduroreel with its gearing and drag brake, just like a big multiplier fishing reel (however, they are said to be less robustly-built than the Rutland reels). Note the central handle.

Contact details below

Contact details below

Gallagher Reels

3:1 gear ratio for smooth operation. Drag brake prevents overrun and reduces tangling. Ratchet lock prevents accidental dispensing. Reels easily removed for quick replacement. Longer crank handle ensures easier winding. Twin hooks for hanging reel on fence. Reel capacity 500m

Standard Economy Reel

Standard Economy Reel

With direct drive. Lightweight for easy handling. Drag brake prevents run-on. Ratchet lock to prevent accidental dispensing. Twin hooks for hanging reel on fence. Reel capacity 500m of fencing wire

Gallagher also makes a small capacity reel holding 200m, the Handi Reel

Gallaghers Reels and Reel Systems

Available locally across the UK

Web: Gallagher Reels

Geared Reels

"Equipped with an accelerator mechanism so the drum rotates three times faster compared to a standard reel for fast spooling. Carry handle with knuckle guard to protect hands. Locking ratchet. Long crank arm for better leverage. Wire loop for connecting power to wire/tape."

Attachable to Reel Stand (consisting of: Reel\Termination Post, Steelpost Reel Connector, and optional Support Bracket).

Commercial electric reels

An expensive luxury or a godsend... it depends on individual priorities balanced with budgets. Imagine a box or framework holding a car battery (good for 2 weeks on a single charge), with a handle on top to which is mounted a large-capacity deep sea fishing reel powered by a smooth, controllable electric motor.

Such systems are in use, and can bring a kite down from a thousand feet in around 3 or 4 minutes. They are equally good for launching and climbing.

Electromate Technotron Systems makes one using Penn reels.

Homemade electric reels and winders

Left: here's an example of a homemade electric drill-powered reel, designed and crafted by falconer Ed Schaub in the mid 1990s. Ed says his latest winders are simpler than this - easier to make.

Left: here's an example of a homemade electric drill-powered reel, designed and crafted by falconer Ed Schaub in the mid 1990s. Ed says his latest winders are simpler than this - easier to make.

Below - These have to be the simplest powered winders ever. Roger Crandall sent this picture of his two reels - one for light line, one for heavy. "I've been flying a Little Bear for three years now and have just about worn it

out."

Dave Scarbrough uses a home-made system consisting of a steel drum mounted in a cubical frame of welded steel, powered by a rechargeable drill. It weighs about 60 lbs, so it acts as an effective anchor.

Dave Scarbrough uses a home-made system consisting of a steel drum mounted in a cubical frame of welded steel, powered by a rechargeable drill. It weighs about 60 lbs, so it acts as an effective anchor.

One falconer regularly flies to 2,000 feet using a boat winch.

Here is a battery-powered boat winch, mounted on an old golfbag trolley. The gearing is modified to give a good rate of descent, and it is controlled manually through a wired handset.

More on reels

A word about knots

Regardless of what reels or winders you use, or what kind of line, bear in mind they won't be any stronger than the weakest links - the knots. It pays to do some digging to find and learn a few good, handy knots. Fishermen have an arsenal of favorite knots, but for the rest of us a good little knot book is a most useful reference. Be sure to use one that indicates the relative strengths of the various knots, and look for knots between 90 or 95 and 100% efficiency. Many common knots actually reduce the breaking strain by as much as 50% or more.

More kites are lost through line breakage than all other possibilities combined. Always keep an eye on the full length of flying line as it's wound out and in, watching for any signs of damage, which, if found, should be cut out on the spot.

Some useful knots

SnapAway Linkages - Home - Contents - Catalogs - How-to section

Kites for falconry - Colors - Opinions - Bird control

Top of page

©1998-2015

©1998-2015

Dan Leigh, 54 Osborne Road, Pontypool, Gwent, Wales, UK NP4 6LX

Many people have said they didn't think they could manage the kite flying aspect of this. Their fear is rooted in a perception or dim recollection of a time long ago when all attempts to get a kite flying were met with disaster. This depressingly common state of affairs is most likely caused by the fact that commercial kites are made to sell, not necessarily to fly (with thanks to The Popular Recreator, 1872-3). Rest assured that a decently made, well designed delta kite is very easy to get aloft. There are no adjustments. Assembly is just one cross-piece to insert. They fly themselves. Launching is straightforward, usually no more difficult than letting the line run out with a little drag. Once they're up, they stay put, and can be tied off to a ground anchor.

Many people have said they didn't think they could manage the kite flying aspect of this. Their fear is rooted in a perception or dim recollection of a time long ago when all attempts to get a kite flying were met with disaster. This depressingly common state of affairs is most likely caused by the fact that commercial kites are made to sell, not necessarily to fly (with thanks to The Popular Recreator, 1872-3). Rest assured that a decently made, well designed delta kite is very easy to get aloft. There are no adjustments. Assembly is just one cross-piece to insert. They fly themselves. Launching is straightforward, usually no more difficult than letting the line run out with a little drag. Once they're up, they stay put, and can be tied off to a ground anchor.

Helping Roger James out at a falconry display I attached one of Roger's small metal terry clips (made for cupboard doors) to my line about 80 feet down from the kite using a

Helping Roger James out at a falconry display I attached one of Roger's small metal terry clips (made for cupboard doors) to my line about 80 feet down from the kite using a

Gerry Plant uses this little downrig, based on one originally devised by Andy Hollidge. It is utterly reliable. The little pulley has ball bearings.

Gerry Plant uses this little downrig, based on one originally devised by Andy Hollidge. It is utterly reliable. The little pulley has ball bearings.

Little Bear 76.5in x 47in/1.94 x 1.20m

Little Bear 76.5in x 47in/1.94 x 1.20m  Wildcard 88in/2.24m span; for high angle flying in breezy weather

Wildcard 88in/2.24m span; for high angle flying in breezy weather

Whirlwind 100in/2.54m span; light to medium winds

Whirlwind 100in/2.54m span; light to medium winds

Clipper S solid color

Clipper S solid color  Trooper RS - solid color

Trooper RS - solid color

CC345 S solid color

CC345 S solid color  R5 Rustler 70in/1.79m span; medium to fresh winds

R5 Rustler 70in/1.79m span; medium to fresh winds

R6 7ft 4in/2.24m span; for lightish breezes to quite windy conditions

R6 7ft 4in/2.24m span; for lightish breezes to quite windy conditions

The birds associate kites with treats, and they can get to know the color of their own kite, but they're primarily interested in the lures, and they can see whether there's a lure up there or not, even one the size of a thumbnail.

The birds associate kites with treats, and they can get to know the color of their own kite, but they're primarily interested in the lures, and they can see whether there's a lure up there or not, even one the size of a thumbnail.

Contact details below

Contact details below

Standard Economy Reel

Standard Economy Reel

Left: here's an example of a homemade electric drill-powered reel, designed and crafted by falconer Ed Schaub in the mid 1990s. Ed says his latest winders are simpler than this - easier to make.

Left: here's an example of a homemade electric drill-powered reel, designed and crafted by falconer Ed Schaub in the mid 1990s. Ed says his latest winders are simpler than this - easier to make.

Dave Scarbrough

Dave Scarbrough